Rimsky-Korsakov: The Flight of the Bumble-Bee

Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition, Promenade

Antonín Dvorák: Symphony No. 9, ‘From the New World’

Edvard Grieg: Morning

Claude Debussy: LA FILLE AUX CHEVEUX DE LIN

Rimsky-Korsakov: The Flight of the Bumble-Bee

Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition, Promenade

Antonín Dvorák: Symphony No. 9, ‘From the New World’

Edvard Grieg: Morning

Claude Debussy: LA FILLE AUX CHEVEUX DE LIN

Ludwig van Beethoven: Bagatellen, Opus 33 ,,Für Elise” W o O 59 | 27th April 1810

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 – Ode to Joy

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 8, Second Movement (Pathétique)

Frédéric Chopin: Prelude in D Flat, Op. 28 No. 15, ‘Raindrop’

Frédéric Chopin: Berceuse, Opus 57

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 101, ‘Clock’

Wolgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Sonata No. 11, ‘Andante Grazioso’

Wolgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 23, Second Movement (Adagio)

Antonio Vivaldi: Gloria in excelsis Deo

Johann Sebastian Bach: Toccata in D Minor BWV 565

Johann Sebastian Bach: The Art of the Fugue, Contrapunctus 1

Johann Sebastian Bach: Lord, Though A-While in Tears of Sorrow from St. Matthew Passion

Richard Farnaby: Fain would I wed

Traditional/Bobb: Scarborough Fair

Dowland: “Come Again… Sweet Love Doth Now Invite”

Michael Angelo Bobb

______________________________________

Reading time, excluding videos, equals:

______________________________________

Two components:

Abstract

What is communication? What is the church? What is a Christian? The research here does not include empirical data collection methodology or analysis of individual case studies. What is used, however, are the semiotic theories of two philosophers in the discourse of communication. The key terms – ‘Church’ and ‘Christianity’ – has been researched, and semiotics has been applied thereafter. My own musical composition, and ekphrastic – ne plus ultra1 – poetry, are included in this document to support the research. I am in favour of the intellectual, and of the spiritual economic, regarding matters of faith. This is built upon my own lifelong experiences, and those that stretches beyond the scope of this research project. I am also aware that there are the illiterate, and those at either end of the socio-economic/affluence dichotomy. Some research authors, and other intellectual persons may exclude these categories of people from knowledge. It must be stated that knowledge can be communicated – and exchanged – between human beings and the Devine, nonetheless… Before the concluding chapter, I supply a specific history of photography that is relevant to the research project. This provides context for the practical creative work. The practical creative work is an online photomedia playlist, titled: The Well-tempered Church. The music that has been used in the designed videos are all major key fugues2 from: the Well-tempered Clavier by Johann Sebastian Bach. Naturally, the ideas of what key signatures are meant to portrait has changed over time. Bach, arguably, is history’s greatest composer. In his compositions he communicated as if: “from God to man”. Also during the epoch before semiotic theory was discovered, the composer George Frideric Handel completes the bi-directional religious communication, i.e. as if: “from man to God”. Further definitive research is required on this vertical, possibly: TO WHAT EXTENT CAN MUSIC COMMUNICATE CHRISTIANITY?

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1: COMMUNICATION, CHRISTIANITY, AND CONTEXT

Understanding Communication

Historical Context: Church Art and Communication

Christianity: Origins and Core Beliefs

Scope and Parameters of This Study

Important Limitation

CHAPTER 2: KEY TERMS—RELIGION, CHURCH, AND CHRISTIANITY

Defining Religion

Defining Church: Etymology and Biblical Foundation

Greek Origins

The Nature of the Church

Invisible Yet Visible

Church Buildings

Orientation: Facing East

The Reformation and Counter-Reformation

CHAPTER 3: SEMIOTICS – THE THEORY OF SIGNS

Communication as Meaning Generation

Semiotics: The Study of Signs

Three Main Areas of Study in Semiotics

The Role of the Reader

Defining the Sign

Founders of Semiotics: Peirce and Saussure

Peirce’s Model

Peirce’s Categories of Signs

Limitations of Semiotic Models

CHAPTER 4: ANALYSIS OF CHURCH ART AND DESIGN

Introduction

Symbolism of Numbers

Spiritus Sanctus, Opus 13

Symbolism of Colours

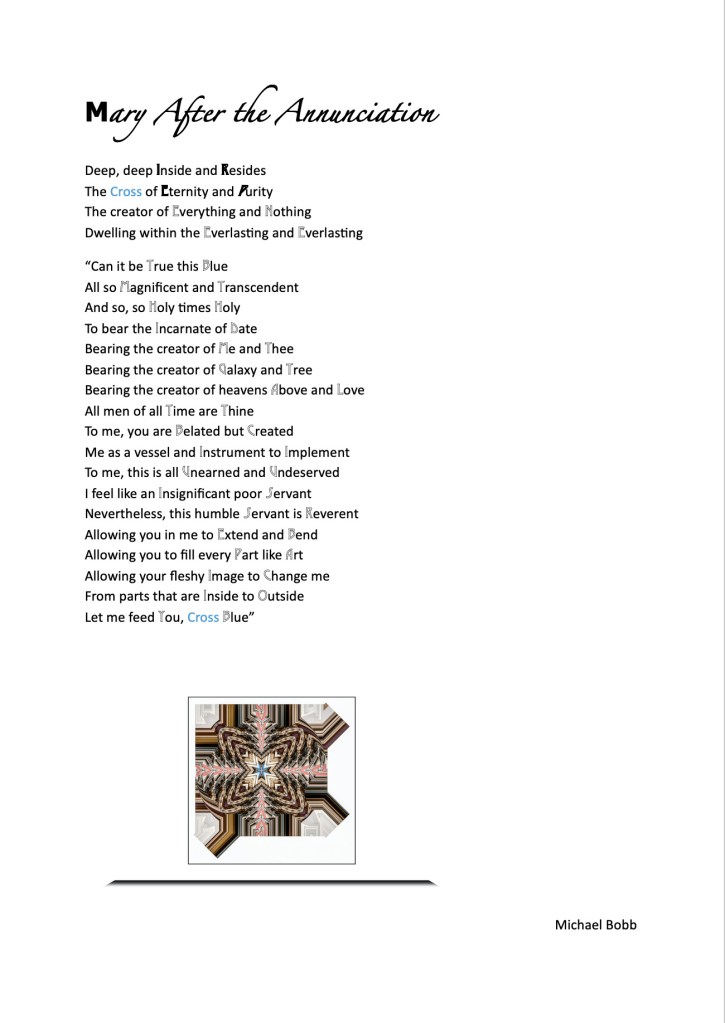

Mary After the Annunciation

Analysis of Specific Photographs

A Stained Glass Window

The Erpingham Chasuble

Description

Heraldry and Historical Context

Semiotic Analysis

Bishop Foxe’s Crozier

Description

Key Features

Semiotic Analysis

CHAPTER 4A: ARCHITECTURAL PHOTOGRAPHY AND CHURCH BUILDING MAGAZINE

Architecture and Photography: Common Characteristics

Cathedrals: Mirroring the Power of God

The Architect’s Role and Training

History of Architectural Photography

The Dry Plate Revolution

The Magazine Era

Modernism and Experimental Photography

Colour Photography Era

Understanding Architectural Drawings

Church Building Magazine

Issue 86 (March/April 2004) Overview

— EDITORIAL SECTION

— PROJECTS SECTION

— FEATURES SECTION includes six articles

— ADVERTISING FEATURES

Issue 90

— A selection of geometric abstract images by Michael Bobb featured

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION

Recapitulation

The Historical Role of Art in Christian Communication

Why Iconic Art is Symbolic

The Invisible Yet Visible Church

What Can Be Communicated Through Visual Media

Future Research Possibilities

FINAL ANSWER: TO WHAT EXTENT CAN IMAGES OF CHURCH ART AND DESIGN COMMUNICATE CHRISTIANITY?

What Can Be Communicated

Limitations of Communication

The Role of the Reader

Conclusion

SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE STUDY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Table of Figures

Fig. 1: Model of Communication

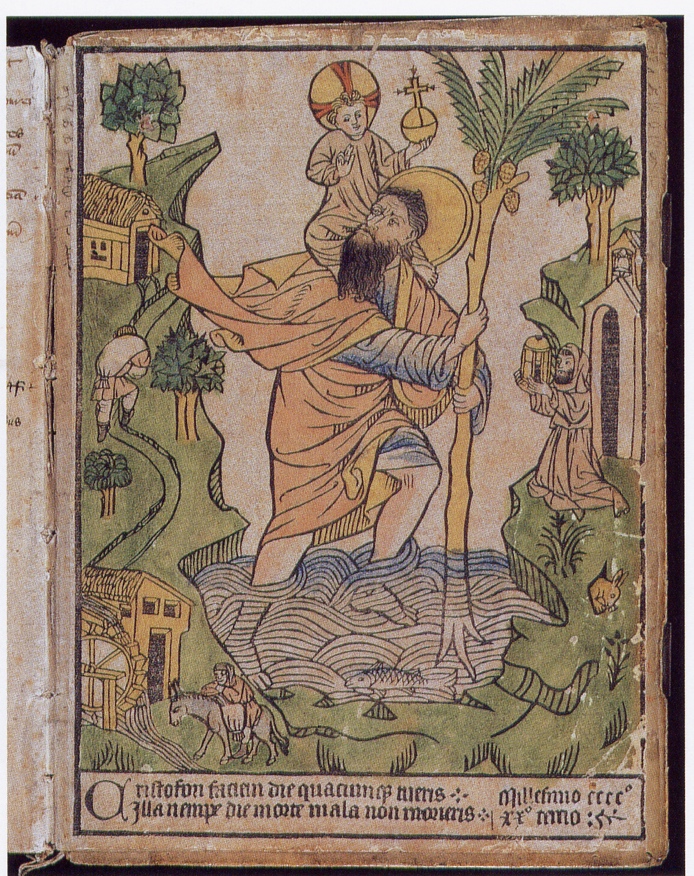

Fig. 2: Saint Christopher Woodcut

Fig. 3: Peirce’s Elements of Meaning

Fig. 4: Peirce’s Categories of Sign Types

Fig. 5: Crossroads Road Sign

Fig. 6: Pulpit at St. Mary’s, Eaton

Fig. 7: Spiritus Sanctus, Opus 13 (video link)

Fig. 8: Ekphrastic Poem

Fig. 9: Stained Glass Window (Panel Perpendicular Tracery, 1485-1509)

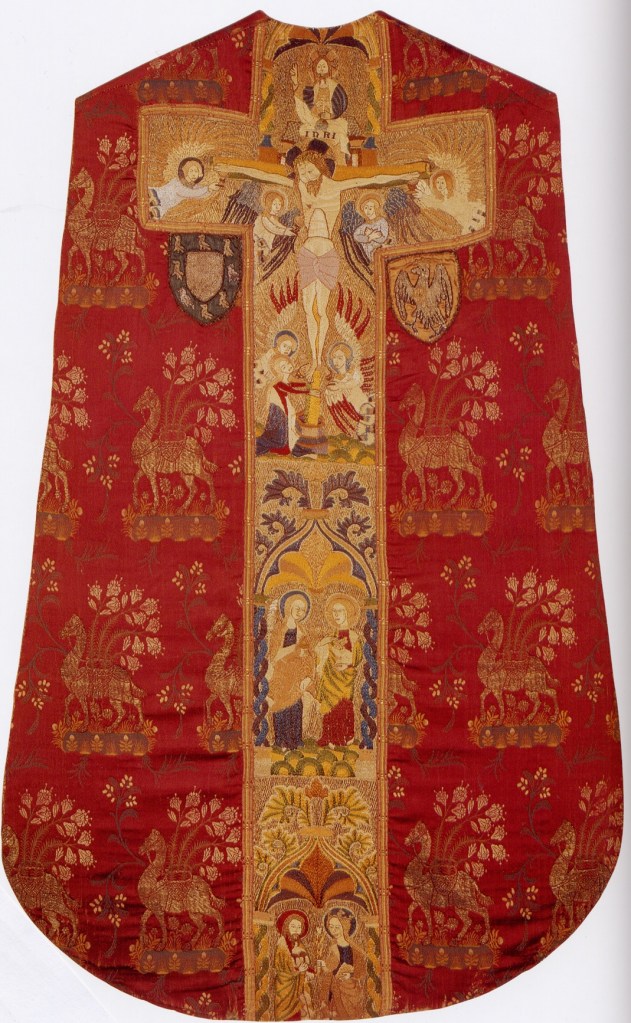

Fig. 10: The Erpingham Chasuble

Fig. 11: Bishop Foxe’s Crozier

Fig. 12: Leighton House, London, 1895

Fig. 13a: Existing Communion Service arrangements

Fig. 13b: Computer enhanced image Service arrangements

Fig. 13c: Before work carried out

Fig. 13d: After work carried out

i

Dissertation

TO WHAT EXTENT CAN IMAGES OF

CHURCH ART AND DESIGN

COMMUNICATE CHRISTIANITY?

CHAPTER 1: COMMUNICATION, CHRISTIANITY, AND CONTEXT

Understanding Communication

Human communication is something everyone recognizes. It encompasses:

– Talking to one another

– Television

– Spreading information

– Our hairstyle

– Literary criticism

The list is endless. All communication involves signs and codes. (Fiske, 2001:1).

In this dissertation, communication will be seen as the production and exchange of meanings. Messages, or texts, interact with people to produce meanings – that is, communication is concerned with the role of texts in our culture (Fiske, 2001:2).

The message or text is an element in a structural relationship whose other elements include:

– External reality

– The producer/reader

“Producing and reading the text are parallel, if not identical, processes in that they occupy the same place in this structured relationship.” (Fiske, 2001:3).

A model of this structure can be visualized as a triangle:

MESSAGE/TEXT

/ \

/ \

/ \

REFERENT —- PRODUCER/READER

Fig. 1: Model of Communication

At the center of this triangle is MEANING, with bidirectional arrows connecting to all three corners. This structure is not static but dynamic, where the arrows represent constant interaction.

Historical Context: Church Art and Communication

In history, church art and design represented the pinnacle of human creativity. The inherent message of Christianity was communicated to people who were illiterate or poorly educated. The arts, including photography, are not restricted by the barriers of verbal communication and can reach deep into people’s hearts and minds, creating an experience of Christianity.

Throughout this dissertation, photographs of church art and design will be used to determine how this subject matter communicates Christianity.

Christianity: Origins and Core Beliefs

Christianity started in the Roman province of Palestine (present-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan) and is based on the life, teachings, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Although Jesus only taught for three years and died an apparently humiliating and painful death on the cross outside Jerusalem, his birth is now celebrated around the world as the point from which time is measured.

As Keen writes:

Christianity grew initially as a radical movement within the much older tradition of Judaism. Jesus was a Jew and remained faithful throughout his life to the Jewish faith, but after his death, the new religion spread more widely among the Gentiles than the Jews. Christianity thus developed a life of its own, apart from its mother faith, although the link between the two remained complex and problematic for a long time. As Christianity spread beyond the Roman Empire, the life and teachings of Jesus remained at the heart of the faith.

(Keen, 2002:6)

Christians believe that:

– Jesus is God, or the Son of God

– He became incarnate to restore the relationship between God and mankind that had been broken by human sin

– When Jesus was crucified and rose again, he broke the hold of sin and death

– Today he reigns as Lord of all creation

Christians can:

– Have a personal relationship with God through Christ

– Live in the power of the Holy Spirit

– Belong to a community of believers

– Respond to the radical teachings of Jesus

On church membership, Keen observes: “Today Christianity is the world’s largest religion with some 1,500 million followers throughout the world” (Keen, 2002:7).

Scope and Parameters of This Study

Although Christianity is a worldwide religion, this dissertation uses photographs of church art and design based in the UK. When deciding which images to include, history was no barrier. Where the message is most clear, illustrative, and interesting, and where pieces of work are photographed to a high standard, they are more likely to appear within these pages.

These images are photographs – representations of a representation. That is, they portray, depict, symbolize, or present the likeness of the subject matter, and are therefore secondary source material as opposed to primary source material. The subject matter itself portrays, depicts, or symbolises something – in this case, aspects of Christianity.

Important Limitation

“Aspects of Christianity” means not the whole of Christianity. The whole of Christianity involves believing in and experiencing the persons of God, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit. Aspects of the church are also unseen. The church here means a community of believers, and God is the only one who knows who the true believers are. In this respect, the research is limited.

Having said this, the research will attempt to investigate what can be registered on film and submit an analysis of what is being communicated. The contents of the message can bring about a particular understanding or revelation that results in change, which can be seen as evidence. This will be looked at later in this dissertation.

Chapter 2 examines the meanings of key terms that appear in the central question. It opens with Christianity, connecting it to religion. Religion is discussed before moving to the next key term: church.

The term “church” is unpacked starting with its Greek origins and continuing with biblical references. What emerges is that the church is the local or worldwide collective of saints. A saint is a person recognized for the holiness of their life – “holy” means dedicated to God and applies to all true Christians. The church is also, among other things, invisible yet visible.

Chapter 2 also investigates:

– The origin of church buildings

– Orientation in traditional churches (e.g., facing east for worship)

– The Reformation and Counter-Reformation

– A synopsis of Christianity

Chapter 3 examines the communication theory of semiotics – the study of signs and the way they work. Examples used to illustrate the theory are taken from terms in the central question: images, church art and design, communication, and Christianity.

The three main areas of study within semiotics are:

– The sign itself

– The codes or systems into which signs are organized

– The culture within which these codes and signs operate

The founders of semiotics – Peirce and Saussure – will be examined, with focus on Peirce. Peirce divided his theory into two models:

– Elements of meaning

– Categories of sign types

Chapter 4 analyses specific photographs. The opening gives a taste of meanings and aspects of Christian art and design. Following this, there will be examination of essential groundwork necessary to read the photographs, such as the meaning of:

– Numbers

– Shapes

– Colours

– Halos

The photographs analysed include:

– A stained-glass window with panel perpendicular tracery design

– The Erpingham Chasuble

– Bishop Foxe’s Crozier

Chapter 5/Conclusion expands on:

– Recipients of messages expressed in church art and design

– How church art and design can assist and enrich the Christian experience

– Why iconic art is symbolic and what it is based upon

– The invisible yet visible essence of the church

– The extent to which images of church art and design communicate Christianity

CHAPTER 2: KEY TERMS—RELIGION, CHURCH, AND CHRISTIANITY

Defining Religion

A key term in this dissertation is “Christianity” which cannot be dissociated from religion. Before defining Christianity, we must discuss religion.

The Collins Concise Dictionary (2001) defines religion as:

According to Émile Durkeim, religion is viewed as an essential set of collective representations of social solidarity.

Terry Eagleton states: “Religion… is probably the most ideological of the very institutions of civil society” (Eagleton, 1998:113).

Louis Althusser continues:

“…religious ideology is addressed to individuals in order to ‘transform them into subjects’, by interpellating the individual… with a personal identity… [who recognizes] a destination (eternal life or damnation)… God defines himself as he who is free, himself and for himself (‘I am that I am’)… ‘God will recognise his own…’ [the Holy Family], i.e. those who have recognized themselves in Him, will be saved.”

(Evans and Hall, 1999:322)

Defining Church: Etymology and Biblical Foundation

Now that this is established, another key term in the central question – church – will be examined to understand what the term actually means and what it does not mean or imply.

Greek Origins

We need to look at the etymology of the word. In the Greek New Testament, the word used is ekklesia, which appears in the Septuagint but not in the Hebrew Canon as an equivalent for “congregation” in the Old Testament.

Stephen’s speech in the Bible makes this connection in Acts 7:38: “He was in the assembly…” (Barker, 1987:1623). In this sense, it has been adopted to describe the new gathering or congregation of disciples of Jesus Christ.

In the Gospels, the word is only found in Matthew 16:18 and 18:17.

In Acts, the situation is one where the saving work has been fulfilled and the New Testament church has its birthday at Pentecost. From here, the term “church” is used to describe local groups of believers. The Bible makes references to:

– The church at Jerusalem (Acts 5:11)

– Antioch (13:1)

– Caesarea (18:22)

The word is also used for all believers. From its inauguration, the church has both local and general significance, denoting both the individual assembly and the worldwide community.

The Nature of the Church

For Christians:

“… the church is not primarily a human structure like a political, social, or economic organism. It is basically the Church of Jesus Christ – “my church” (Matthew 16:18) – or of the living God (1 Timothy 3:15). (Douglas and Tenney, 1987: 219)”

And again:

“It is a building of which Jesus is the chief cornerstone or foundation, ‘a holy temple in the Lord… a dwelling in which God lives by his Holy Spirit’ (Ephesians 2:20-22). It is the fellowship of saints or people of God (1 Peter 2:9). It is the bride of Jesus Christ, saved and sanctified by him for union with himself (Ephesians 5:25-26). Indeed, it is the body of Christ, he being the head of the whole body. It is the fullness of Christ, who himself fills all in all (Ephesians 1:23).”

(Ibid.)

Invisible Yet Visible

An important essence of the church is that it is invisible, yet visible:

“In its true spiritual reality as the fellowship of all genuine believers, the church is invisible. This is because we cannot see the spiritual condition of people’s hearts. Also, the invisible church is the church as God sees it.”

(Grudem, 1994:855)

Whereas there are elements of metaphor and imagery in some terms used to refer to the church, its true reality is found in the company of those who believe in Jesus Christ. They believe they themselves are, in a sense, dead, buried, and raised with him, their Savior.

Church Buildings

From this understanding of the church, it follows that ‘church building’ is interchangeable with the word ‘church,’ both terms meaning a building for public Christian worship. The buildings came about as the church grew.

The stories of the New Testament tell of large assemblies in the open air, which to an extent still occur (e.g., Billy Graham crusades, papal masses, Salvation Army gatherings). Even after the Disruption – the great split in the Scottish Presbyterian Church in 1843 – many newly formed Free Church congregations were without buildings for decades.

The earliest communication sign was usually a cross marking their meeting place:

“Itinerant priests would hold services at the cross, which would usually be set up at a convenient place in the center of the community or by the wayside. Such preaching crosses are often preserved, sometimes inside churches…”

(Cunningham, 1999:44)

Orientation: Facing East

When the early church started building places to meet, they followed similar practices to synagogues. Almost universal customs developed regarding orientation:

– East and South were the honoured sides

– North and West were not

Facing eastward for worship – the direction in which the sun rises – is a practice that is pre-Christian. There are biblical references to God in the East, e.g., “the glory of the Lord was coming from the east” (Ezekiel 43:2).

This position acknowledges the symbolism of Christ, the Son of righteousness, rising to heaven just as the sun rises in the east (Cunningham, 1999:150).

Additionally:

“It was also the case that for most Christians, since faith developed around the Mediterranean, east was the direction of Jerusalem, which in the eyes of medieval cartographers was the centre of the world.”

(Ibid.)

The longitudinal axis of most churches is therefore west-east. The plan shows it as a cross, with:

– Entrance on the west side

– Altar on the east

As the community worships, it usually faces eastward. Images that express Christian hope are often depicted in the east stained-glass window. The west side was considered the best place for doom paintings of the Last Judgment.

In much the same way:

– Light on the south was preferred to the dark north

– The right-hand side was seen as good

– The left was bad (the Latin word for left, sinister, now means ‘suggestive of evil’)

The Reformation and Counter-Reformation

Church history encountered a major disturbance in the 16th century known as the Reformation. This movement was known as Protestantism because they protested against the Roman Catholic Church, calling it spiritually bankrupt. This led to the creation of important Protestant denominations such as:

– Lutheranism

– Calvinism

– Presbyterianism

In England, Henry VIII rejected the authority of the Pope and established the Anglican Church.

The Reformation had opposing effects on church arts:

In Protestant churches:

– Architecture was plainer and less ornate

– Imagery avoided sources outside the Bible

– In some cases, iconoclasts smashed imagery in churches

In Roman Catholic churches (Counter-Reformation):

– Imagery and symbolism became even more emphasized and elaborate

CHAPTER 3: SEMIOTICS – THE THEORY OF SIGNS

Communication as Meaning Generation

Communication is the generation of meaning. When Person A communicates with Person B, Person B understands, more or less accurately, what the message means.

For communication to take place:

– Person A must create a message out of signs

– This message stimulates Person B to create a meaning

– The more these two people share the same codes and sign systems, the closer their meanings approximate each other

Therefore, taking the central question: for the communication of Christianity’s meaning to take place, God’s messages in church art and design signs must be examined to investigate their limits.

These photographs are intended to stimulate understanding—albeit limited—for any reader that relates in some way to the author’s intention.

Semiotics: The Study of Signs

At the center of this consideration is the sign. The study of signs and the way they work will be examined from the theoretical perspective of semiotics.

Semiotics is the study of signs and the way they work and relate the structure of texts to social systems, examining how meanings are made. The part signs play within cultural processes relates messages to both social experience and the social system in general. Because of this, semiotics can be grouped under the term “the human sciences.”

Three Main Areas of Study in Semiotics

1. The sign itself

– The study of different varieties of signs

– The different ways they convey meaning

– The way they relate to the people who use them

– Signs are human constructs understood in terms of the uses people put them to

2. The codes or systems into which signs are organized

– How various codes have developed to meet the needs of a society or culture

– How they exploit the channels of communication available for their transmission

3. The culture within which these codes and signs operate

– Dependent upon the use of these codes and signs for its own existence and form

(Fiske, 2001)

From this, we can see that semiotics is primarily concerned with texts.

The Role of the Reader

In semiotic theory, the status of the receiver or reader is seen as playing an active role. The term “reader” is preferred to “receiver” because it implies:

– A greater amount of activity

– That reading is something we learn to do, determined by the cultural experience of the reader

In their thinking and behaviour, the reader helps create the meaning of the text by bringing to it different aspects of individual background, including:

– Gender

– Age group

– Family

– Class

– Nation and ethnicity

– Education

– Religion

– Political allegiance

– Region

– Urban versus rural background

(Price, 2002:186)

Defining the Sign

A sign is regarded as:

– Something physical and perceivable by the senses

– It refers to something other than itself

– It depends on recognition by its users that it is a sign

Fig. 2: Saint Christopher Woodcut

The woodcut in Figure 2 is a sign of Christian art. In this case, the sign refers to the story of Saint Christopher and is recognized as such by both the craftsman and anybody familiar with the account. Meaning is conveyed from the craftsman to a person with understanding of the story—communication has taken place.

Founders of Semiotics: Peirce and Saussure

There are two founders of semiotics:

– C.S. Peirce, the American logician and philosopher

– Ferdinand de Saussure, the Swiss linguist

Peirce is preferred over Saussure when addressing the subject matter of this lecture.

Peirce’s Model

C.S. Peirce identified a triangular relationship between the sign, the user, and external reality as a necessary model for studying meaning.

Peirce explained:

“A sign is something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity. It addresses somebody – that is, it creates in the mind of that person an equivalent sign, or perhaps a more developed sign. That sign which it creates I call the interpretant of the first sign. The sign stands for something, its object.”

(Fiske, 2001:42)

SIGN

/ \

/ \

/ \

OBJECT —- INTERPRETANT

Fig. 3: Peirce’s Elements of Meaning

(with bidirectional arrows between all three elements)

A sign:

– Refers to something other than itself (the object)

– Is comprehended by somebody (has an effect on the mind of the user—the interpretant)

The interpretant is not the user of the sign but what Peirce terms “the proper significate effect.” It is a mental concept produced both by the sign and by the user’s experience of the object.

For example, the interpretant of the word “church” will be the result of the user’s experience of that word – they would not apply it to a mosque – and their experience of churches (the objects). This definition is not fixed but may vary according to the experience of the user. The limits are set by social conventions (such as the English language), though variations within them allow for social and psychological differences between users.

Peirce’s Categories of Signs

Another fundamental aspect of semiotics is that there is no distinction between encoder and decoder – decoding is as active and creative as encoding.

Looking further into Peirce’s model, he divided signs into three categories:

ICON

/ \

/ \

/ \

INDEX —- SYMBOL

Fig. 4: Peirce’s Categories of Sign Types

(with bidirectional arrows between all three)

Peirce writes:

“Every sign is determined by its object, either first, by partaking in the character of the object, which I call the sign an icon; secondly, by being really and in its individual existence connected with the individual object, which I call a sign an index; thirdly, by more or less approximate certainty that it will be interpreted as denoting the object in consequence of a habit, which I call this sign a symbol.”

(Fiske, 2001:47)

Icon: A sign resembling its object in some way – it looks or sounds like it (e.g., a high-quality portrait)

Index: A sign with a direct link between the sign and its object – the two are connected (e.g., the finger of God pointing to man, the creation, showing relationship)

Symbol: A sign whose connection between itself and its object is a matter of convention, agreement, or rule (e.g., a crucifix or cross)

Example: Road Sign

These categories are not isolated and definitive. Any particular sign may be composed of various categories.

Fig. 5: Crossroads Road Sign

According to the Highway Code:

– The red triangle is a symbol (warning)

– The cross in the middle is a combination of icon and symbol:

– Iconic because its form is determined partly by the shape of its object

– Symbolic because we need to know the rules to understand it as “crossroads” and not “hospital” or “church”

– In real life, the sign is an index in that it indicates we are approaching a crossroads

The positioning of this road sign in this lecture is not indexical – it is not physically/spatially connected with its object.

Church buildings are inseparably and greatly iconic because they convey Christianity through form, and the end result of professionally executed design is highly iconic.

Why Peirce Over Saussure?

Peirce’s idea as a philosopher was concerned with people’s understanding of their experiences and the world around them. This theory is relevant to this discussion by way of meaning (e.g., agency found in directional signs, judge’s rulings, Christians as people, objects like crucifixes).

Saussure, alternatively, was a linguist primarily interested in language. His work was connected with the way signs (or words) related to other signs. He was less concerned with Peirce’s “object.”

For Saussure, a sign consisted of:

– Signifier: the sign’s image as we perceive it (marks on paper or sounds in the air)

– Signified: the mental concept to which it refers (Fiske, 2001:43-44)

When comparing these two models, there are similarities between:

– Saussure’s signifier and Peirce’s sign

– Saussure’s signified and Peirce’s interpretant

However, Saussure is not suitable because he is less concerned with the relationship of those two elements and with Peirce’s object or external reality.

Limitations of Semiotic Models

Despite Peirce’s semiotic theory being appropriate for this lecture, it has limitations:

1. These models of semiotics use words that refer to what we can see and hear—our senses and environment – and do not take into consideration basic tenets of Christianity such as:

– The invisible and spiritual

– God

– The supernatural world

– Belief

1. I believe Peirce was writing from an American perspective based on American education, which comes through in the words he used in his theory.

I suggest to everyone receiving this lecture to consider reading and investigating other similar theories and other books apart from Fiske’s ‘Introduction’ (2001). Although Saussure and Peirce were founders of semiotic theory, our understanding requires broader reading.

CHAPTER 4: ANALYSIS OF CHURCH ART AND DESIGN

Introduction

Some churches are full of meaning. Aspects of Christianity are seen in:

– The heavenly-pointing spire on the outside

– Carvings around the entrance speaking of holiness

– The interior, particularly the nave, which makes a symbolic contrast between the worldly world outside and the sanctuary within

– The altar drawing one forward

– Pews on either side forming a gangway like a ship carrying worshippers to God

– The altar, the heart of the building, contained in a separate and sacred space

In this chapter, analysis of photographs of church art and design will be carried out. The messages they communicate relate, in some cases, to major central doctrines of Christianity.

When reading the photographs, there are significant Christian ideas, history, and principles that occur regularly, such as:

– Numbers

– Shapes

– Colours

– Halos

According to Peirce’s theory, they will be grouped under the categories of sign types. Equipped with this knowledge, the reader will be able to understand images for themselves.

Symbolism of Numbers

One (1)

The circle was considered by the ancient Greeks to be the perfect shape – eternal, without beginning or end, infinite, and whole. Therefore, a single circle is a symbol of the divine or eternal. The number 1 expresses the unity of God. (Taylor, 2003:14)

Two (2)

Used in reference to the Old and New Testaments, or to the human and divine natures of Jesus.

Three (3)

Used as a symbol of the Trinity, particularly in connection with an equilateral triangle. This type of triangle represents the equality of the three persons of the Trinity. It can also represent the three days Jesus’s body spent in the tomb before resurrection.

Four (4)

Represents:

– The four Evangelists

– The four rivers that Genesis said flowed from Eden: Pishon, Gihon, Tigris, and Euphrates (Genesis 2:10-14)

– The four horsemen of the Apocalypse (Revelation 6):

– Conquest (white horse, rider crowned, carrying a bow)

– War (red horse, rider carrying a sword)

– Famine (black horse, rider carrying scales)

– Death (pale green horse, rider usually skeletal)

(Taylor, 2003:14)

The solid, unmoving form of a square or cube is a symbol for the earth as it was perceived before the Age of Enlightenment. However, it should be noted that David refers to the earth as spherical, and Job mentions how the earth is suspended – Job being the first book written before Genesis, suggesting knowledge of the earth’s shape and position among heavenly bodies was known before it was depicted in art history.

Five (5)

Symbolizes the five wounds Jesus suffered in the crucifixion: the nails in his hands and feet and the spear in his side. (Ibid.)

Seven (7)

Significant, powerful, and associated with perfection, e.g.:

– God resting on the seventh day after completing creation

– Jacob bowing seven times before his brother Esau as a sign of perfect submission (Genesis 33:3-4)

– God ordering that the lampstand for the Tabernacle should have seven branches (Exodus 25:37)

– The seven angels blowing their trumpets in the Apocalypse (Revelation 8-11)

(Ibid.)

Eight (8)

The shape of an octagon is a symbol of Jesus unifying God and earth. An octagon is halfway between a circle (God) and a square (earth). Just as Jesus was the incarnation of God on earth, so the octagon mediates between the two. (Taylor, 2003:14-15)

This idea of heaven and earth coming into contact is behind the octagonal shape of some fonts and pulpits.

Fig. 6: Pulpit at St. Mary’s, Eaton

Taylor continues: At the baptism of a person, heaven and earth touch, while during a sermon the preacher is hopefully communicating the word of God.

Nine (9)

The number of angels, since there are nine choirs of them.

Ten (10)

The number of the Ten Commandments.

Twelve (12)

In a church, refers to:

– The twelve disciples, which in turn referred to the twelve tribes of Israel

– Since in both instances it is a number of a group of people dedicated to God, it is sometimes used to represent the whole church

Thirteen (13)

Ominous and indicates betrayal, since it was the number of people present around the table at the Last Supper.

(Taylor, 2003:15)

Spiritus Sanctus, Opus 133

Spiritus Sanctus, Opus 13 was composed by myself – and when translated from Latin to English, means: Spirit Holy. Scored for soprano, soprano recorder, violin and harpsichord.

Fig. 7: Spiritus Sanctus, Opus 13 video link

Symbolism of Colours

Colours can have symbolic meanings within traditional interpretations of church arts:

“Black Sickness, death, and the devil, but also mourning…

“Blue Traditionally associated with the Virgin Mary and also with Jesus. Blue is the colour of the sky and represents heavenly love.

“Brown … renunciation of the world.

“Gold … the colour of light, has the same symbolic meaning as white, with which it is often used.

“Green … the colour of earth, and in particular the triumph of life over death…

“Grey The colour of ashes, symbolizes the death of the body, repentance, and humility. In paintings of the Last Judgment, Jesus is sometimes shown wearing grey.

“Purple … the colour of penance, royalty, and imperial power. For this reason, God the Father is sometimes shown in a purple mantle.

“Red … the colour of Pentecost, the colour of passions. It can mean hate or love, although it is most often used for the latter. Jesus is often shown in a red cloak. As the colour of blood, red is often used for the robes of martyrs.

“White … the colour of purity and innocence, spiritual transcendence. At Jesus’s Transfiguration (Matthew 17:2), the angels at the resurrection were dressed in white (Matthew 28:3). Silver can be used instead of white.

“Yellow … used as a variant of white, represents light and is a common colour for halos in stained glass. It can, though, also indicate an infernal light of treachery and deceit. Judas Iscariot is sometimes portrayed wearing yellow.

(Taylor, 2003:17-18)

Mary After the Annunciation

Ekphrastic poem written by myself where blue represents Jesus Christ:

Fig. 8: Ekphrastic Poem4

Halos

The halos that appear in church art are positioned around the head of a person of particular spiritual power. Although halos themselves are, in semiotics, a sign type symbolizing something non-physical – they communicate holiness and divine favour.

Analysis of Specific Photographs

Fig. 9: Stained Glass Window (Panel Perpendicular Tracery, 1485-1509)

The overall shape and design of this stained-glass window dates between 1485 and 1509 and is called a panel perpendicular tracery.

Tracery is the term used to describe the varied forms of stone and glass decoration of the window head during the Middle Ages. Designs developed and finally led to the panel perpendicular type. Each part of the design was shaped in small concave arcs of stone called foils. The number of foils was indicated by the prefix: trefoil (3), quatrefoil (4), cinquefoil (5), or multifoil (many). (Dirsztay, 2004:231)

Figure 10 has many smaller arcs and is therefore a multifoil design.

This stained-glass window shows iconic signs of the Christian faith in three scenes:

Left scene: The appearance of the risen Christ to the Virgin Mary

Middle scene: The Transfiguration

Right scene: The three Marys at the sepulchre

At this point, it must be noted that the first and last scenes are extra-biblical. Having said this, there are accounts of the risen Jesus showing himself to women at the sepulchre, recorded in Matthew, Mark, and John (but not Luke).

Matthew 28:9-10 (NIV):

“Suddenly Jesus met them [Mary Magdalene and the other Mary]. ‘Greetings,’ he said. They came to him, clasped his feet and worshiped him. Then Jesus said to them, ‘Do not be afraid. Go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee; there they will see me.’”

Mark 16:9 (NIV): “When Jesus rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene…”

John 20:14, 16 (NIV):

“… she [Mary Madgdalene] turned around and saw Jesus standing there, but she did not realize that it was Jesus… Jesus said to her, ‘Mary. She turned toward him and cried out in Aramaic, ‘Rabboni!’ (which means Teacher).”

A Stained-Glass Window Analysis

These accounts do not mean that the scenes in the stained-glass window are not communicating Christianity. In fact, some Christian art, as mentioned in Chapter 2, has inspiration from sources outside the Bible.

Symbolic signs for the two outer scenes of this window include:

– Gold divine circle halos for Jesus (the colour of light)

– White for the women (the colour of purity and innocence)

In the clothing, the symbols are:

Left scene:

– Jesus’s cloak is purple, which represents royalty

Right scene:

– Jesus’s cloak is red, indicating love or meditating on Jesus’s spirit

– Blue for the Virgin Mary

– White covering red for Mary Magdalene, indicating purity and innocence covering her love

– Green around the sepulchre means the triumph of life over death

– Blue is also the colour of the sky and represents heavenly love

Middle section: The Transfiguration scene

This scene contains iconic signs and is recorded in Matthew, Mark, and Luke of the Bible.

Mark 9:2-4 (NIV):

“After six days Jesus took Peter, James and John with him and led them up a high mountain, where they were all alone. There he was transfigured before them. His clothes became dazzling white, whiter than anyone in the world could bleach them. And there appeared before them Elijah and Moses, who were talking with Jesus.”

Symbolic signs:

– Gold hands, feet, and halo for Jesus (the colour of light)

– His white clothes showing spiritual transcendence

– Colours apply to Elijah and Moses at the feet of Jesus

– Jesus’s brown robe indicates renunciation of the world or a particular manifestation of God’s power, such as the Transfiguration itself

– Jesus and Moses embody the colour of the sky and represent heavenly love

– The three disciples in the bottom section are, as documented in Mark 9:6, frightened

Fig. 10: The Erpingham Chasuble

The Concise Oxford Dictionary (1992:190) defines a chasuble as: “a loose sleeveless outer vestment worn by a priest celebrating Mass or the Eucharist.”

Description:

The silk design features an oriental fantasy of gold camels bearing flower baskets, in the international courtly style favoured in the late 14th and 15th centuries. The embroidered orphrey (decorative band) shows Christ crucified and pairs of saints beneath decorated arches.

Heraldry and Historical Context:

The chasuble bears:

– The shield of arms of Sir Thomas Erpingham (died 1428) under the cross (all three on the left)

– His personal devices on the right:

– An eagle rising inscribed with the words “Think and Thank”

– A red rose of Lancaster

Sir Thomas Erpingham championed the Lancastrian cause and achieved high office under both Henry IV and Henry V, acquiring land and property in London and Norfolk. Although the chasuble cannot be identified among the records of many vestments that Sir Thomas gave to Erpingham, Norfolk, and other churches, it may have been made for his personal chaplain or for a church with which he was connected. (Marks and Williamson, 2003:410)

Semiotic Analysis:

Chasubles that were originally decorated and included the heraldry of the donor or patron were commonly used as symbols of secular power and spiritual authority. Using the language of semiotics, the decoration contains iconic signs of the Passion of Jesus Christ and both spiritual and worldly matters.

The chasuble communicates:

– Religious devotion through the crucifixion imagery

– Social status through the heraldic devices

– Political allegiance through the Lancastrian symbols

– Wealth and patronage through the quality of materials and craftsmanship

Fig. 11: Bishop Foxe’s Crozier

Figure 12 shows the top section of Bishop Foxe’s Crozier.

The Concise Oxford Dictionary (1992:276) defines a crozier as: “a hooked staff carried by a bishop as a symbol of pastoral office.”

Description:

“One of the earliest surviving English late medieval silver pieces, this impressively architectural example was made for Bishop Richard Foxe (c 1448-1528) and is decorated on the upper knop and the crook in black enamel with his personal badge and his arms.”

(Marks and Williamson, 2003:241)

Key Features:

“… its most telling feature is perhaps a series of 12 apostle figures around the architectural part of the crozier, but these came from the same casting patterns used for the finials of early sixteenth century apostle spoons. The sees of Exeter and Winchester were both dedicated to Saint Peter, whose seated figure appears prominently within the curved crook…”

(Marks and Williamson, 2003:241)

Semiotic Analysis:

The bishop’s hooked staff is a rich iconic representation of the shepherd type used by Jesus Christ himself, being the “Good Shepherd” (John 10:14).

The crozier communicates:

– Pastoral authority through the shepherd’s crook form

– Apostolic succession through the twelve apostle figures

– Episcopal office through the architectural grandeur

– Personal identity through the heraldic devices

– Connection to Saint Peter as the first bishop and keeper of the keys

The elaborateness of the crozier is a lavish and accomplished piece of human art, but only a dimmed representation or sign of Christ’s greatness and glory.

The degree to which Christianity can be communicated in comparison to photographs of church art and design will be expanded in the following Chapter 5/Conclusion.

CHAPTER 4A: ARCHITECTURAL PHOTOGRAPHY AND CHURCH BUILDING MAGAZINE

Architecture and Photography: Common Characteristics

Architecture and the medium of photography share the common characteristics of art and science at the same time. “Patient study and careful observation” (Michal Harris quoting Frederic H Evans from 1900, 2002:6) must be the foundation stones of successful architectural photography, along with sufficient technical knowledge and experience to be able to render the: “subtle and recondite charm” (ibid.) of a building. An informed appreciation of church buildings should generate a helpful and positive awareness in the photographer’s approach, resulting in enhancing the relevance and aesthetic value of their photographs depicting Christianity.

The readership of such photographs can be almost anybody who either professes Christianity or not. This is because these buildings:

– Represent the zenith of architecture in times past

– Stand out from the environment because of their design

– Are often higher than anything in the vicinity

– Were places where the community gathered to worship or engage in other activities

Cathedrals: Mirroring the Power of God

With churches, particularly cathedrals (a cathedral is the seat (cathedra) of a bishop), the buildings had to be grandiose in order to mirror the power of God.

“As places of worship they needed to reflect the glories of heaven, and enabled the liturgy to be as reverent and impressive as possible.”

(Stollard, 1993:2)

In some cathedrals, the soaring verticals dominate, avoiding wherever possible horizontal lines. This is because there is a longing for immortality and the worship of God.

Also, in some of these buildings:

“The powerful dynamic effect achieved in the interior was based upon a single principle: the columns supporting the great arcades, the ceiling, and the floor decoration should all combine to draw the eyes of the congregation to the altar. Light filtering through the many openings high up in the walls should accentuate these upward tensions…”

(Erlande-Brandenburg, 1993:9)

The Architect’s Role and Training

In this present era, the work of an architect is to design buildings and supervise the construction procedure. This task is complex, and students train for seven years to become qualified because they have to learn how to integrate the social and technological aspects involved in the design and construction of a building. (Harris, 2002)

Today, students must:

– Acquire detailed knowledge of the physical laws and properties of a multitude of different materials

– Realize the structural properties of each material

– Assimilate knowledge of heating, lighting, ventilation, and air conditioning

– Learn the service requirements for buildings: water, heating, drainage, and sewage

– Develop an intellectual understanding of the history of architecture

– Study the huge diversity of building types (houses, offices, hospitals, factories) with their respective building and safety regulations

– Acquire the skills of competent draftsmanship

(Ibid.)

In their occupation, the architect is both:

Creator: of visually satisfying and technically sound buildings for specific purposes

Coordinator: of the subsequent construction with planners, engineers, and contractors, taking overall responsibility for monitoring their successful construction on site

History of Architectural Photography

The historical development of architectural photography can be dated to 1826 when Nicéphore Niépce took the first photograph.

After:

– Louis Daguerre’s daguerreotype invention in 1839

– William Henry Fox Talbot’s rival calotype negative-positive process in 1841

Both employed buildings as their subject matter because they were ideal for the long exposures required at this time.

The Dry Plate Revolution

Occurring at the same time, companies were beginning to be formed specializing in photographing contemporary architecture, both inside and out.

During the 1870s, gelatin dry plates were produced for commercial use, which meant that:

– The location photographer did not need a portable darkroom (as with the wet collodion process)

– Development could occur long after exposure

– The plates were more sensitive to light, allowing shorter exposure times

The best-known company in England to take advantage of this was: “Bedford Lemere & Co., who set the standard for others to follow [see Figure 13]” (Harris, 2003:3)

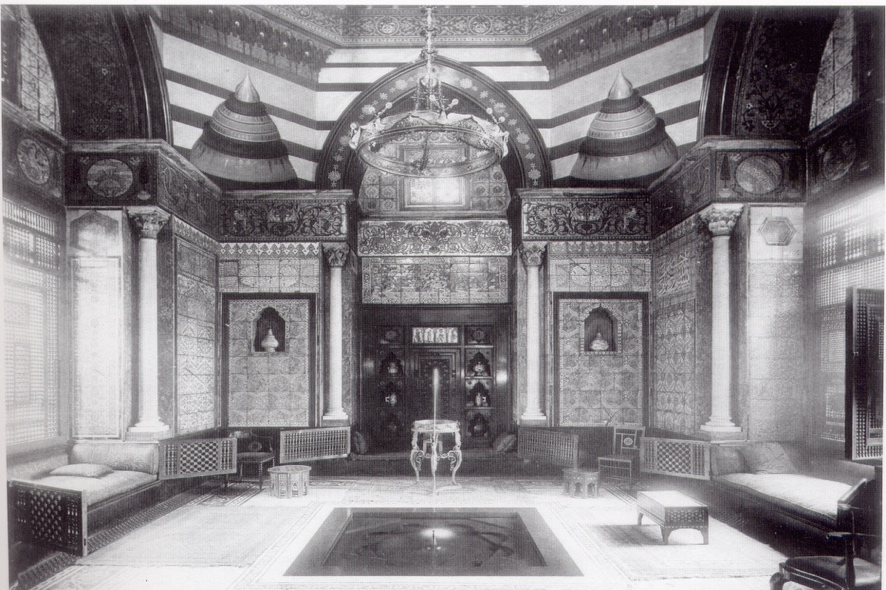

Fig. 12: Leighton House, London, 1895

The Magazine Era

In the 1890s, there was a great increase in new magazines with the introduction of halftone printing, making it possible to print photographs and type together in one operation.

Country Life magazine’s photographer, Charles Latham, created its tradition of fine country house photography. (Harris, 2003:5-6)

Frederick H. Evans also appeared in Country Life. He was well known for his interiors, believing that his true aim as a photographer was to:

– Record emotion

– Convey the sensations, both spiritual and aesthetic, that medieval architecture aroused in him

He abandoned all-inclusive compositions for a more fragmentary approach, preferring to use the longest focal length possible to create views through different parts of buildings, recording subtle graduations of light and shade within these medieval interiors. This approach is still seen in modern interior magazine photography to this date. (Ibid.)

Modernism and Experimental Photography

The 1920s and 1930s saw experimental and utopian optimism in architecture. The clinical lines and forms of modern architecture suited more abstract photography, encouraging dramatic lighting and camera angles.

This is found in the work of:

– The Dell and Wainwright partnership, who were official photographers to Architectural Review from 1930 to 1946

– Sydney Newbery, the official photographer for the Architects’ Journal from 1920

Point of interest: Architects faced criticism for imitating photographers – building with lights and shadows in black and white – thereby underlining the reciprocal relationship that existed between photography and architecture at this time. (Ibid.)

Colour Photography Era

The widespread use of colour photography from the 1970s, combined with the growth of:

– Interior magazines

– Property brochures

– Illustrated annual reports

… have given photographers and designers more creative opportunities.

Understanding Architectural Drawings

In many architectural and building publications, features and projects include photographs and design drawings. Therefore, it is useful to have an understanding of terms used in them, including being able to interpret what is shown.

The main types of design drawing are:

– Plan

– Site plan

– Elevation

– Section

– Perspective

– Axonometric projection

– Isometric projection

– Working drawings

Church Building Magazine

For the remainder of this chapter, one journal will be brought into focus: Church Building.

This journal was entering its 21st year at the time of writing the dissertation (2004) and overviews on a regular basis what is happening in and around ecclesiastical places of worship.

Issue 86 (March/April 2004) Overview

To acquire a flavour of the contents, Issue 86 will be looked at more closely. Its 80 pages are divided into four sections:

1. EDITORIAL SECTION includes:

– Viewpoint (written by the editor)

– Letters (where readers have their say)

– In View (containing details of the El Greco (1541-1614) exhibition at the National Gallery, running until May 23, 2004)

– Questions and Answers (based on seating in churches)

2. PROJECTS SECTION (34 pages):

Contains details of building, conservation, and conversion projects. Contacts and entries are listed in alphabetical order and can be added by writing to the editor.

There are 12 churches written about, both nationally and internationally, with:

– Colour and black-and-white photographs

– Elevations

– Artist impressions and design drawings

Most projects include details about:

– Architects

– Consultants

– Engineers

– Contractors

– Quantity surveyors

3. FEATURES SECTION includes six articles:

– London and the Church: 1000 Years On

– Mystic Gardens

– Books Reviewed

– John Piper’s House and Studio / National Gallery’s East Wing

– An Appreciation: “One Man’s World of Lettering”

– John Shaw: A Man of Eternal Letters (a graduate of Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts, involved in design and lettering for churches since 1970)

4. ADVERTISING FEATURES (three features):

a) Scaffolding Solutions (Layher and Haki Staging):

About a new demountable sanctuary staging system for the church choir, placed immediately in front of the choir steps. The feature includes:

– Before the work was done

– Computer-generated images

– After completion

(See Figures 13a, 13b, 13c, 13d)

Figure 13a Figure 13b

Existing Communion Computer enhanced image

Service arrangements

Figure 13c Figure 13d

Before work carried out After work carried out

b) Lightning Conductor Engineering (ATLAS):

About the new name of what used to be the National Federation of Master Steeplejacks and Lightning Conductor Engineers (NFMSLCE), now the Association of Technical Lightning and Access Specialists (ATLAS). This feature is in question-and-answer interview format.

c) Masonry Matters:

About acting now to preserve the future of architectural and craft training courses, written by an education officer at the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB).

All the above features are within the journal’s ethos – that is, containing elements of Christian places of worship.

CHURCH QUADRATURES

In 2004, a selection of my quadrature images featured in Church Building magazine, Issue 90.

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION

Recapitulation

In Chapter 1, there was an introduction into communication – what people recognize it to be and what it involves. Communication is the production and exchange of meanings. This was followed by an introduction into Christianity: what it is and where it came from. This was necessary to prepare for the following chapters.

That chapter also informed the reader, according to semiotic theory, certain key concepts to be considered when deciding particular church art and design. This was also the case when choosing the photographs that are included within the pages of the dissertation. What was also considered involved understanding the term: representations of a representation.

Chapter 2 examined the two key terms from the central question: church and Christianity.

Chapter 3 looked at semiotics, where the work of Peirce was the main focus of attention.

In Chapter 4, photographs of church art and design were semiotically analysed.

The Historical Role of Art in Christian Communication

In bygone years, Christians communicated their message to largely illiterate or poorly educated believers by means of the arts as shown in the previous chapters. “The arts can break through communication barriers by direct approach to people’s hearts and minds.” (Momen, 1999:455)

In this way, the arts have always been an important aspect of the manner in which Christianity is communicated. In many cultures, Christian art used to be the main way of teaching people the history and doctrine of the faith.

For the Christian, it is the experience of Christianity that is of greatest importance, and this important experience can be assisted by encountering church art.

Why Iconic Art is Symbolic

Iconic forms of art are still, to a large extent, symbolic.

The use of the term ‘icon’ here means, according to Keen:

“A painting of Jesus Christ, the Holy Family, or one of the saints, used in the Eastern Orthodox Church as an aid to devotion in church and in the home.” (Keen, 2002:156)

The term symbolic refers to the non-literal representation.

The reason why iconic art is symbolic is because it takes people beyond themselves to the truth that it represents.

Momen writes:

“That truth being beyond human understanding, traditional artists are content merely to allude to it simply. They are not concerned with making the icon seem lifelike. Indeed, to do so would distract from the purpose of the work of art. Iconography is based upon a sense of order in the universe, the authority of tradition and the hierarchy of the established cosmology.”

(Momen, 1999:465)

The last sentence of this quote – “iconography… cosmology” – can be interpreted as: church art communicates Christian ideas.

In Christianity, such art is to be found not only in the icons of the Eastern Orthodox Church but also in the painting, sculpture, architecture, calligraphy, and manuscript illumination of cultures in the world as diverse as Britain and Syria.

The Invisible Yet Visible Church

In Chapter 2, I stated that an important essence of the church is that it is invisible, yet visible.

Here is the limit to what photographs of church art and design can communicate presently:

– We can see people (whom we judge)

– We can see the outward evidence of inward spiritual change

– But we cannot see into people’s hearts and their true spiritual state – only God can do that

In fact, if God is sovereign, then it means that he has, and is, working in the life of the Christian (Ephesians 2:10), and therefore they bear his fingerprint.

Also, this view of the church is not restricted to this particular understanding. When considering the church as visible and invisible:

In eternity, it is invisible. The writer of Hebrews speaks of:

“The assembly [literally ‘church’] of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven” (Hebrews 12:23)

…and says that present-day Christians join with that assembly in worship.

However, this topic of the invisible church is not accepted in all quarters of the universal church.

Grudem writes:

“Both Martin Luther and John Calvin were eager to affirm this invisible aspect of the church over and against the Roman Catholic teaching that the church was the one visible organization that had descended from the Apostles in an unbroken line of succession through the bishops of the church. [In more precise terms, the Roman Catholic Church]…(Grudem, 1994:855)

On the other hand, Grudem points out:

“… the true church of Christ certainly has a visible aspect as well. We may use the following definition: The visible church is the church as Christians on earth see it. In this sense, the visible church includes all who profess faith in Christ and give evidence of that faith in their lives.”

(Grudem, 1994:856)

What Can Be Communicated Through Visual Media

With this definition, Christianity and church life can be communicated using visual recording media.

Also, as the project stands, it has succeeded in analysing the representations in the photographs, and meanings have been conveyed.

In Chapter 4, for example, the pulpit in Figure 6 communicates the idea of heaven and earth coming into contact with each other. However, to take this idea on board, there must be a belief in the unseen reality of heaven.

Future Research Possibilities

The relationship between photographs and the communication of Christianity could be pursued further by the documentary genre. This genre is more suitable for the task and would be in the form of:

– Photographic essays accompanied with written text

– Moving images

Both media must include testimonies by the portrayed of their lives:

– Before they became Christians

– As Christians today

If theoretical analysis were undertaken in this case, it would use ideology as a framework.

Ideally, if it were possible, there could be a piece of work that included documentation of people’s lives that contrasted:

– The old way of life

– With the new abundant life

This would document the journey from what is visible to what is invisible.

FINAL ANSWER: TO WHAT EXTENT CAN IMAGES OF CHURCH ART AND DESIGN COMMUNICATE CHRISTIANITY?

What Can Be Communicated

Images of church art and design can communicate Christianity to a significant extent by conveying:

1. Theological Doctrines:

– The Trinity (through triangular forms and groups of three)

– The Incarnation (through octagonal shapes mediating between heaven and earth)

– The Resurrection (through green symbolizing triumph of life over death)

– The Passion of Christ (through crosses, wounds, and red colouring)

2. Biblical Narratives:

– Stories from the Gospels (Transfiguration, Resurrection appearances)

– Lives of saints and apostles

– Old Testament types and New Testament fulfilments

3. Spiritual Realities:

– Holiness (through halos and gold)

– Purity (through white and silver)

– Divine love (through blue and heavenly imagery)

– Pastoral care (through the Good Shepherd imagery)

4. Church Identity:

– Apostolic succession (through the twelve apostles)

– Ecclesiastical authority (through episcopal symbols)

– Community worship (through architectural directing of attention to altar)

5. Devotional Aids:

– Focus for prayer and meditation

– Visual teaching for the illiterate

– Inspiration for worship

– Connection between earthly and heavenly worship

Limitations of Communication

However, there are inherent limitations:

1. The Invisible Spiritual Reality:

– Images cannot show the true spiritual condition of hearts (only God knows this)

– They cannot convey the full experience of God, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit

– They cannot replace personal faith and relationship with God

2. Semiotic Limitations:

– Require cultural knowledge to decode properly

– Depend on the reader’s experience and background

– Are representations of representations (secondary sources)

– Can be misinterpreted without proper context

3. The Transcendent Nature of Truth:

– Divine truth is beyond human understanding

– Art can only allude to rather than fully represent spiritual reality

– Images are signs pointing beyond themselves, not the reality itself

4. The Need for the Holy Spirit:

– Ultimate communication of Christianity requires the work of the Holy Spirit

– Transformation of life cannot be captured fully in static images

– The “invisible church” remains beyond photographic documentation

The Role of the Reader

The extent to which images communicate Christianity also depends heavily on what the reader brings:

– Knowledge of Christian teaching and symbolism

– Cultural and historical context

– Openness to spiritual truth

– Personal faith experience

– Familiarity with biblical narratives

As Peirce’s semiotics demonstrates, the interpretant – the mental concept produced by the sign – requires the user’s experience and understanding.

Conclusion

To directly answer the central question:

Images of church art and design can communicate Christianity extensively and effectively, but not completely.

They serve as:

– Powerful educational tools for teaching doctrine and history

– Aids to devotion that inspire and focus worship

– Cultural expressions of faith across time and place

– Signs and symbols pointing to deeper spiritual truths

However, they remain limited by:

– Their material and visual nature

– The invisible, spiritual essence of true faith

– The need for interpretation and context

– Their status as representations rather than reality itself

The fullness of Christianity – the living faith, transformed life, and encounter with the living God – remains a mystery that transcends visual representation, even as it often begins with what the eye can see.

As the bishop’s crozier demonstrates: it is “a lavish and accomplished piece of human art, but only a dimmed representation or sign of Christ’s greatness and glory.”

In this way, images of church art and design are windows through which we glimpse truth, but they are not the truth itself. They are fingers pointing to the moon, not the moon itself.

For the layperson and believer alike, these images serve their purpose when they draw us beyond themselves to the reality they represent – to worship, devotion, understanding, and ultimately to God himself.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE STUDY

Future research could pursue:

– Documentary photography combining images with personal testimonies of transformed lives

– Comparative studies of how different Christian traditions use visual communication

– Reception studies examining how different audiences interpret church art

– Digital media and newer forms of visual communication that are sympathetic to Christianity

– The relationship between iconoclasm and communication theory

– Cross-cultural studies of Christian visual communication beyond Western contexts

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, M.D., (1995), History and Imagery in British Churches, London, John Murray (Publishers) Ltd.

Barker, K., (ed.), (1989), The NIV Study Bible, Great Britain, Hodder and Stoughton Limited.

Brandenburg, D., (1993), [Cathedral architecture reference]

COLLINS CONCISE DICTIONARY, (2001), Glasgow, HarperCollins Publishers.

THE CONCISE OXFORD DICTIONARY, (1992), Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Culler, J., (1994), On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism After Structuralism, London, Routledge.

Cunningham, C., (1999), Stones of Witness: Church Architecture and Function, Gloucestershire, Sutton Publishing Limited.

Dirsztay, P., (2001), Inside Churches: A Guide to Church Furnishings. London, NADFAS Enterprises Limited.

Douglas, J.D. and Tenney, M.C. (1987), The New International Dictionary of the Bible, Basingstoke, Marshall Pickering.

Eagleton, T., (1991), Ideology: An Introduction, London, Verso.

Eagleton, T., (1998), Ideology, Essex, Pearson Education Limited.

Evans, J. and Hall, S. (eds.) (1999), Visual Culture: The Reader, London, Sage Publications Ltd.

Fiske, J., (1994), Reading the Popular, London, Routledge.

Fiske, J., (2001), Introduction to Communication Studies, Cornwall, Routledge.

Grudem, W., (1994), Systematic Theology, [Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press]

Hale, T., (1996), The Applied New Testament Commentary, Eastbourne, Kingsway Publications.

Harris, M., (2002-2003), [Architectural photography references]

Keen, M., (2002), Christianity. Oxford, Lion Publishing plc.

Lawton, N., (2004), Church Building, 85:1.

Marks, R. and Williamson, P. (2003). Gothic Art for England, 1400-1547, London, V&A Publications.

Momen, M., (1999), The Phenomenon of Religion, Oxford, Oneworld Publications.

Price, S., (2002), Media Studies, Essex, Pearson Education Limited.

Stalley, R., (1999), [Cathedral architecture reference]

Sturken, M. and Cartwright, L. (2001), Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Taylor, R., (2003), How to Read a Church, London, Ebury Press.

THE AUTHORISED ROGET’S THESAURUS OF ENGLISH WORDS AND PHRASES (1988), Middlesex, Penguin Books Ltd.

Wells, L., (ed.) (2001), Photography: A Critical Introduction, London, Routledge.

ii

Practical creative work5

(click image for YouTube videobook)

Word count: 10,524

Christ Jesus the Beau

Opus 10 No. 10

Chorus

See you later

See you later

Later you see

See you later

Revelation

The Prophet

1st Verse

So, He cocked His weapon did the Beau

And aimed it straight at the foe

Given it both barrels

Obliterating death in one go

Chorus

See you later

See you later

Later you see

See you later

Revelation

The Prophet

1st Verse – Variation

So, He cocked His weapon did the Beau

--- You have had your all

And aimed it straight at the foe

--- And breathed your last breath

Giving it both barrels

--- Terminate you

Obliterating death in one go

Chorus

See you later

See you later

Later you see

See you later

Revelation

The Prophet

2nd Verse

No longer can it terrorise

--- Go and take a hike

Making people run in fear

--- Don’t ever come back

Playing the fear game

--- Terminate you

Finality and end now the same

Chorus

See you later

See you later

Later you see

See you later

Revelation

The Prophet

3rd Verse

Yanked and thrown off the train of life

--- Don’t ever call us

Mustering no resistance

--- And we won’t call you

Destroyed for ever

--- Terminate you

No longer having an existence

Revelation

Revelation

4th Verse – ‘Heaven’s Anthem’

Now, life and love and laughter

Embraces fullness and freedom and fraternity

And creativity and comfort and compassion

Lives in excitement and existence for eternity

4th Verse – ‘Heaven’s Anthem’ Reprise

(Triumphantly)

Now, life and love and laughter

Embraces fullness and freedom and fraternity

And creativity and comfort and compassion

Lives in excitement and existence for eternity

Christ Jesus the Beau

Audio

The Seven Spirits of Christ

Opus 10 No. 9

1st Chorus

Women

Spirit calls

Hungry souls

Angels search

Men

Heaven and Earth

Women

Spirit calls

Hungry souls

Angels search

Men

Heaven and Earth

Women

Spirit calls

Hungry souls

Angels search

Men

Heaven and Earth

Men

Earth, Earth, Earth, Earth

Earth, Earth, Earth, Earth

Spirit calls

Hungry souls

Angels search

1st Verse

Throughout the World

Throughout the World

A trumpet sound

A trumpet sound

Is heard aloud

Is heard aloud

A trumpet sounds

2nd Verse

To Earth He comes

To Earth He comes

Our Lord a bounds

Our Lord a bounds

On greater clouds

On greater clouds

Our Lord a bounds

3rd Verse

Then judgement falls

Then judgement falls

As the Lion roars

As the Lion roars

His tongue projects

His tongue projects

Striking nations

4th Verse

Treading winepress

Treading winepress

Of God’s anger

Of God’s anger

His enemies

His enemies

Cannot escape

Throughout the World

Throughout the World

A trumpet sound

A trumpet sound

Is heard aloud

Is heard aloud

A trumpet sounds

KING AND LORD OF ALL

Solo

King and Lord of all

Our eternal light

For ever is Christ

Our eternal Christ

2nd Chorus

Spirit calls

Spirit calls

Hungry souls

Hungry souls

Angels search

Angels search

3rd Chorus

Spirit calls!

Heaven and Earth!

Heaven and Earth!

Heaven and Earth!

Hea' heaven and Earth!

Calls!

Heaven and Earth!

Heaven and Earth!

Heaven and Earth!

Heaven and Earth!

The Seven Spirits of Christ

Audio

Video Special

Jauchzet Frohlocket – After J.S. Bach

Opus 10 No. 8

"Strings

Strings and trumpets

And trumpets

And trumpets

Strings

Strings and trumpets

And trumpets

And trumpets

Strings

And trumpets

And trumpets

And trum!"

Sing, you choir, loud and clear!

Let your voice be heard

Let it pierce the air

Pierce it once, pierce it twice

Angelic hosts

Angelic hosts

Angelic hosts

Pierce it thrice!

Move decisively

Move decisively

Move decisively

Left and right

Dance the dance

Day and night

From the slayer

Lightning flashes!

From his eye

From the slayer

Flash!

Move decisively

Move decisively

Move decisively

Left and right

Dance the dance

Day and night

From his eye

Lightning flashes!

A time of war

A time of clashes!

The command has come

Slay! Slay! Slay! Slay!

You cannot escape

On that dreaded Day

This high music is for you!

Cue higher music, cue

Let it ring

Clear and clarion!

It is for you and you

It is for you

It is your companion

Move, death angel

To and fro

Let all the people know

Yesterday, tomorrow, today

That you, Lord God

Have come to

Slay! Slay! Slay!

Jauchzet Frohlocket – After J. S. Bach

Audio

The Alternative Three Magi!

Opus 10 No. 7

Everyone

“It was the first century…

and Herod had just lost the

seasonal supermarket chain war

– again…!”

1st Verse

From all the way in Lapland

To Bethlehem with presents

Came Santa Claus and Rudolf

Wearing their bright green panties

Santa Claus gave lace up boots

Much bigger than stocking size

He also gave shaving kit

For when Jesus gets baptised

Mr Spock!

2nd Verse

Mr Spock from the Starship

Came from yonder Galaxy

His gift for the young baby

Was a large tube of Smarties

He also had other gifts

From great planets far and wide

But he lost them all

Oh dear!

When the Starship fell over

3rd Verse

The third wiseman was lanky

He wrote music for the Tsars

Moved from Russia to the States

This Sergei Rachmaninoff

His gift was not all that good

But must be played with left toe

Softly and quietly

A lullaby for a King

A full-size grand piano

Traditional Polish Lullaby

Close your eyes, Jesus, dear

Hush all Your sighing

Mary is holding You

No need for crying

The Alternative Three Magi!

Audio